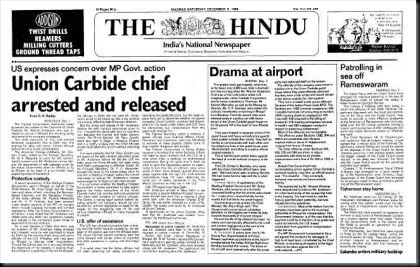

Bhopal: An unsettling settlement

Usha Ramanathan

The course that the law took in cases involving the Centre and Union Carbide Corporation raises several questions.

A survivor of the Bhopal gas tragedy during a demonstration at Jantar Mantar in New Delhi.

The path to the criminal trial and conviction of Keshub Mahindra and six others on June 7, for ‘rash and negligent' conduct that resulted in the death of over 20,000 people and injury and harm to over 5,00,000 people, is full of curious twists and unexplained turns. The dilution of charges in 1996 — from culpable homicide to rashness and negligence — is presided over by a question mark. But the history of this leniency travels further back in time to 1989 when all criminal cases, in process and that may arise in future, in relation to the Bhopal gas disaster were quashed by the Supreme Court when Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) paid $470 million. In February 1989, the court said this would “enable the effectuation of the settlement.” But in December 1989, another bench of the court found that the Claims Act, under which the government had taken over the litigation, had nothing to do with the criminal cases, and that part of the settlement did not derive from the Act but was beyond it. And in 1991, the court, unable to sustain the quashing of criminal cases, backtracked and the criminal cases were revived. This was before the dilution of the charges in 1996. The quashing of criminal cases continues to be shrouded in a mystery that could be resolved if those who were part of the settlement proceedings could be called upon to reveal what they know.

A chronology:

In the beginning, there was the law. In March 1985, Parliament enacted the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act. This gave the Central government the exclusive right to “represent, and act in place of every person who had made a claim, or was so entitled to make a claim, for all purposes connected with such claims in the same manner and to the same effect as such person.”

On February 14, 1989, while an appeal relating to interim compensation was pending before it, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court found “this case is pre-eminently fit for an overall settlement … covering all litigations, claims, rights and liabilities … related to and arising out of the disaster.” So it “ordered” that UCC pay $470 million and, “to enable the effectuation of the settlement,” all civil proceedings would “stand concluded in terms of the settlement” and “all criminal proceedings related to and arising out of the disaster shall stand quashed wherever they may be pending”. The next day, advocates for the Union of India and UCC and Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) filed “Consequential Terms of Settlement” which included a clause that read “and all such criminal proceedings including contempt proceedings stand quashed and accused deemed to be acquitted.”

On May 4, 1989, propelled by protests led by victims' groups and their supporters, the Supreme Court explained how it had arrived at the sum of $470 million. But about the “part of the settlement which terminated the criminal proceedings,” the court declined to say anything since review petitions challenging the settlement were already in court and it “might tend to prejudge this issue one way or the other.”

A 1986 challenge to the Claims Act of 1985 had not been heard before the settlement order was passed. Victims had contested the power of the state to take away their right to litigate. The Supreme Court heard this case in the brooding shadow of the settlement. The judgment of the court in this case, dated December 22, 1989, was categorical that “the criminal liability arising out of the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster is not the subject matter of this Act and cannot be said to have been in any way affected, abridged or modified by virtue of this Act.” “Clearly, therefore” the judges explained, “this part of the settlement comprises a term which is outside the purview of the Act.” Further, the court records the Attorney-General as having told the court that “these are not the considerations which induced the parties to enter into settlement.”

On October 3, 1991, a five-judge bench pronounced its decision on the review petition filed by the victims and their supporters. Of the five judges who constituted the original bench, Justice Pathak had moved to the International Court of Justice not long after the Bhopal settlement order, and Justice Venkataramiah had taken over as the Chief Justice and retired by the end of the year. But Justices Ranganath Misra, Venkatachaliah and N.D. Ojha were still on the bench, with Justices K.N. Singh and Ahmadi joining them. In the time that had elapsed since the settlement order, the government had changed and, with it, the government's position on the settlement order had undergone revision. It was then left to the three judges from the original bench and Fali Nariman, who was UCC's counsel, to recall what had transpired. But that was not to happen. Instead, memory and record were substituted by conjecture.

First, the court declared that it had the constitutional power, located in Article 142, to do “complete justice,” and no statute could undermine this power of the court. So, if the court in its discretion decided that quashing criminal cases was in the interests of complete justice, it had the power to do just that. Then, acknowledging that “the order terminating the pending criminal proceedings is not supportable” strictly in law, the court drew on Mr. Nariman's submission “that if the Union of India as the dominus litis through its Attorney-General invited the court to quash the criminal proceedings and the court accepting the request quashed them, the power to do so was clearly referable to Article 142(1) read with the principle under Section 321 CrPC which enables the government … to withdraw a prosecution.” And so on.

The concern then was not about the existence of the power — which, the court declared, did exist — but “one of justification for its exercise.” “No specific ground or grounds for withdrawal of the prosecution having been set out at that stage, the quashing of the prosecutions requires to be set aside.”

So, settling criminal liability was not negotiated under the Claims Act. The government says it had nothing to do with the quashing of the criminal proceedings. The Supreme Court claims to have the power to go beyond law but says it had not been given grounds for doing so at that stage. It does not say why, then, it did what it did. It leaves it in the realm of conjecture: if the government had invited the court, the court may be obliged. So, it would appear, the Supreme Court had quashed the criminal proceedings for no statable reason.

This became clearer with the court explaining that the quashing of criminal proceedings was not a ‘consideration' for the settlement. That is, no party to the settlement was making it a condition without which the settlement would not stand.

Mr. Nariman drew a distinction between ‘motive' and ‘consideration', and the court adopted it, although what is ‘motive' is not explained. If the quashing of the criminal cases was not to help negotiate the settlement and get the company to agree to pay $470 million — which was $120 million more than it had agreed to pay — why was it in the order and in the terms of settlement?

The settlement was not negotiated in open court. If, as the court conjectures, the government asked the court to quash the criminal proceedings, the court would know.

It is imperative that individual and institutional memory be called upon to resolve these opaque aspects of the Bhopal gas disaster.

(Usha Ramanathan works on the jurisprudence of law, poverty and rights.)